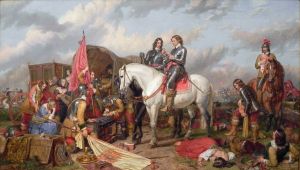

On 14th June 1645, the fields between the Northamptonshire villages of Naseby and Sibbertoft saw one of the most significant battles in British history.

Royalist troops loyal to King Charles I and the Parliamentarian ‘New Model Army’ led by Sir Thomas Fairfax met in the culmination of a three-year bloody civil war that had pitted families and friends against each other and the fates of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland rested in the balance.

So why is The Battle of Naseby so important in British history…?

There are acres and acres of writing about the most “pivotal” moments in history, those occasions when the future seems to turn on a single act and everything after it owes its existence that that moment.

In lists of British history, the Battle of Naseby is one such moment.

Fought on gently sloping fields next to a quiet Northamptonshire village on 14th June 1645 by the Royalist forces of King Charles I and the English Parliament’s New Model Army, Naseby is exactly one of those moments that changed British (and to a certain extent world) history forever.

So what are the top reasons why this battle, in this place, at this time, had such a profound effect?

1. It decided the first English Civil War.

In 1645, the English Civil War could have gone either way – there was no obvious indication that either Parliament nor the Royalists had a clear military advantage over the other. Both sides had large armies filled with a mix of battle-hardened veterans and fresh newbies, plus solid supply bases and well-provisioned garrisons. Although King Charles had lost the North at Marston Moor in 1644, his forces in Scotland were doing well and he still controlled the West and Wales.

Yet his decision to fight the New Model Army at Naseby was arguably one of the single biggest military blunders in British history.

Not only was he heavily outnumbered by Thomas “Black Tom” Fairfax’s New Model Army – 10,000 versus 15,000 – but his men still fought the way they had fought back in 1642 when the war started.

Not only was he heavily outnumbered by Thomas “Black Tom” Fairfax’s New Model Army – 10,000 versus 15,000 – but his men still fought the way they had fought back in 1642 when the war started.

However, Parliament had raised a new army imbued with fresh ideas (see below) and created for one purpose – to strike the decisive blow against the king. At Naseby it did just that.

By concentrating his best forces into one army, leaving his fortified capital of Oxford, and then dithering around in the Midlands, Charles gave Parliament the best chance it had to catch and destroy his forces.

Ironically the battle started well for Charles – Prince Rupert smashed the Parliamentarian left wing with a dashing charge and the King’s pikemen and musketeers pushed Parliament’s infantry back almost to breaking point. However, Rupert’s charge left his men scattered and on the other flank Marmaduke Langdale was routed by Parliament’s golden boy Oliver Cromwell, whose cavalry then turned on the Royalist infantry. A running retreat/rout over 12 miles took place, with thousands of the king’s men captured or killed.

Naseby destroyed the veteran infantry Charles relied on, condemned him to spend the rest of the summer being chased around the Midlands and West Country, and gave the New Model Army the impetus to sweep up the remainder of his forces. Although the King himself believed he could still win the war and fighting dragged on into 1646, his military machine was irrevocably broken and the overwhelming success of the New Model Army at Naseby was the moment King Charles lost the English Civil War.

2. It helped assert the right of Parliament over the monarch.

Ignore what you may have been taught at school – the English Civil War did not start because some people wanted a king and others wanted a republic. That happened, almost by accident, later.

Ignore what you may have been taught at school – the English Civil War did not start because some people wanted a king and others wanted a republic. That happened, almost by accident, later.

But though they may not have known it the men who fought at Naseby were setting their country on the path to both a constitutional monarchy and a modern Parliamentary democracy.

The war had begun as the culmination of a long, drawn-out argument over who controlled the levers of power with few, if any, people arguing for a kingless state. Even before Charles had ruled without Parliament during his ’The Personal Rule’ (also known as the ‘Eleven Years’ Tyranny’ depending on who you asked), MPs had been clamouring for more control over the country, especially with foreign policy, religion, and taxes. That argument eventually boiled over into all out war, which the King would go on to lose.

The victory at Naseby established Parliament’s right to a permanent role in the government of the kingdom.

3. It gave us the Armed Forces.

Before the English Civil War, the British were naturally suspicious of soldiers. To have lots of them hanging around was a recipe for disaster, either because they’d get bored and go on a rampage or it meant the king wanted to use them against his own people. And the people didn’t like either of those options. So armies were only raised when they were needed – either to defend the country or invade somewhere else – and would then be disbanded.

The New Model Army was different.

Before 1645, winning battles mostly came down to good fortune, surprise, soldiers who wouldn’t immediately turn and run (who were common), and commanders who knew what they were doing (who were not). Also, many of the troops Parliament relied upon from London and what we now call the Home Counties had been raised as defensive troops, so as soon as the threat to their counties was over they’d either refuse to move or simply pack up and head home.

The Second Battle of Newbury in October 1644 was a wake up call for Parliament. They had won but only on paper; arguments between the commanders let the King’s defeated forces escape virtually intact. So MPs became convinced that to win the war, rather than several armies led by individual commanders, it needed a single national army committed to the cause. This lead to the New Model Army or, as it was called at the time, “The Army, Newly Modelled”.

To remove political interference in tactical decision making, MPs and Lords(with a few notable exceptions) were forbidden from being officers by the Self-Denying Ordnance while rank was awarded on merit, meaning the brave and militarily gifted rose quickly. Rather than ranks of fresh or conscripted men without adequate arms and provisions, the New Model was to be made up of properly trained, well supplied, and regularly paid professional troops (side note: the latter of these wasn’t exactly followed through).

The New Model Army was Britain’s first professional army and was the beginning of the modern British Army that we know today (in fact, two existing regiments – The Coldstream Guards and The Blues and Royals – can trace their history all the way back to the New Model).

It was a truly revolutionary idea and, at Naseby, it worked.

4. It turned Oliver Cromwell into the historical leviathan we know today.

He’s been dubbed “God’s Englishman” and was voted amongst the top ten Britons of all time but, despite what many think, Oliver Cromwell neither started nor ended the first English Civil War, nor was the conflict “Cromwell vs Charles I”. In fact, he didn’t come to totally dominate English politics until after the King was dead and the second Civil War in 1651 tipped off his beloved and (arguably) more capable superior, Lord Fairfax, as to which way the wind was blowing so that he stood down as leader of the New Model Army.

He’s been dubbed “God’s Englishman” and was voted amongst the top ten Britons of all time but, despite what many think, Oliver Cromwell neither started nor ended the first English Civil War, nor was the conflict “Cromwell vs Charles I”. In fact, he didn’t come to totally dominate English politics until after the King was dead and the second Civil War in 1651 tipped off his beloved and (arguably) more capable superior, Lord Fairfax, as to which way the wind was blowing so that he stood down as leader of the New Model Army.

Cromwell was, however, very good at being a cavalry commander.

At the start of the war in 1642, he was just a lowly Huntingdonshire squire with little in the way of prospects, who only really got elected as an MP because of his family connections. At the outbreak of the war, he organised a local troop of cavalrymen but turned up late to the Battle of Edgehill just in time to witness Parliament’s cavalry get their backsides handed to them by the dashing Prince Rupert’s men.

Cavalry tactics at the time involved two wings of cavalry charging at each other and trying to drive the other side off, the winners then chasing their defeated foes across the countryside in a disordered gallop and maybe stoping off for a pint or two afterwards. Once that initial job was done, the cavalry usually took no more part in a battle. Cromwell realised that if you trained your cavalry properly you could drive off the enemy, get back into order, and then wheel round and attack the enemy’s infantry – and if there’s one thing infantry don’t like, it’s enemy cavalry. Thus were born Cromwell’s elite cavalry, The Ironsides, who turned the tide in pretty much every battle they fought in.

This was certainly the case at Naseby, where he commanded Parliament’s right wing. While Prince Rupert smashed Parliament’s left wing, he couldn’t control his men and by the time they got back to the fighting it was all over – thanks to the Ironsides. Cromwell’s reputation was well on the rise by this point anyway, but Naseby made him a Parliamentarian hero. And the rest, as they say, is history.

(Oh, and for the record he didn’t ban Christmas. Or mince pies. Or dancing. Or the theatre. Or much of anything.)

5. It showed what King Charles was really up to.

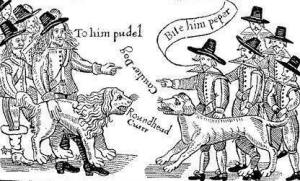

After the battle, the victorious Parliamentarians rampaged through the Royalists ‘baggage train’ – which is where an army keeps its supplies. While capturing great amounts of powder, arms, and food, they also seized the carriage carrying the king’s private papers, which had been left behind in the rout.

After the battle, the victorious Parliamentarians rampaged through the Royalists ‘baggage train’ – which is where an army keeps its supplies. While capturing great amounts of powder, arms, and food, they also seized the carriage carrying the king’s private papers, which had been left behind in the rout.

What it contained was sheer dynamite. Confirming all Parliament’s worst fears and suspicions about Charles, the papers showed that he had been trying to raise an army of Roman Catholic soldiers from Ireland to invade England, as well as negotiating help from French and Spanish mercenaries – all of them also Catholic.

What was wrong with them being Catholic? Bear in mind that Protestant England had been at war with Roman Catholic powers such as Spain and France pretty much ever since Henry VIII had broken from Rome and established the Church of England. Henry and his daughter Elizabeth had mixed Protestantism up with a bombshell cocktail of religious zealotry, national pride, and plain old xenophobia; the despotic reign of Bloody Queen Mary, the Spanish Armada, and the plots against Elizabeth were all still strong in the collective memory and Charles’ dad and King of Scotland, James VI, had only become King James I of England because he was Elizabeth’s closest Protestant relative. So hated were the Catholics that Irish-sounding Royalist soldiers were routinely hanged, Irish-Scottish regiments were given no mercy, and when Parliament’s soldiers overran the Royalist baggage train at Naseby, they infamously raped, mutilated, and killed many of the female camp followers – later justifying it by saying they thought they were Irish Catholics (they undoubtedly weren’t).

Parliament wasted no time in publishing copies of this damning correspondence for the whole nation to see. Charles was shown to not only to be duplicitous but also that he seemingly only cared about being in power and he didn’t care a jot about how he got it.

This moment, combined with his sparking of the second English Civil War by getting the Scottish to invade in 1648, was what sealed his fate and led him to the executioner’s block in 1649.

6. It destroyed the idea of the divine right of kings.

Charles believed, as his father and many others before him, that he was divinely appointed to be king by God himself. Therefore, whatever he wanted to do was – naturally – what God wanted and those who were against him were against the deity himself. Unfortunately, Parliament was becoming increasingly dominated by ultra-devout Puritans who believed THEY were the ones divinely appointed by God and their mission was to overcome the tyranny of fallible Earth-bound kings.

Charles believed, as his father and many others before him, that he was divinely appointed to be king by God himself. Therefore, whatever he wanted to do was – naturally – what God wanted and those who were against him were against the deity himself. Unfortunately, Parliament was becoming increasingly dominated by ultra-devout Puritans who believed THEY were the ones divinely appointed by God and their mission was to overcome the tyranny of fallible Earth-bound kings.

While the war was sparked by issues over forms of worship, money, and power, it soon took on a dangerously dogmatic religious tone. With the removal of their critics in a purged Parliament and the decisive defeat of the King’s army at Naseby, it seemed to the Puritans that God now agreed with them.

After Naseby, the Puritan ‘Independent’ faction would become a political force to be reckoned with. And with one stroke of the executioner’s axe, they irrevocably changed the relationship between England’s monarch and England’s people forever.

7. It was a stepping stone to a political revolution.

In the New Model Army, Parliament had unwittingly created a pet bulldog that it could not control.

Once it had won the war and disposed of the king, and with no military force that could match it, the army quickly came to realise that IT carried the balance of political power and it became a hotbed of radical politics and discontent. Many, including political agitators within the army dubbed Levellers (because, their critics claimed, they wanted to bring rich and poor to the same level), demanded a greater say in government and a famous meeting called The Putney Debates in 1647 was the first time common people and their social superiors had sat down to discuss the very question of the nation’s governance.

It hinged on the question of why had they fought in the first place. Surely, said leading Leveller sympathiser and friend of Cromwell Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, even the lowliest Englishman has the same right to a say in England’s affairs as the highest?

It hinged on the question of why had they fought in the first place. Surely, said leading Leveller sympathiser and friend of Cromwell Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, even the lowliest Englishman has the same right to a say in England’s affairs as the highest?

This, and The Leveller’s idealism, has echoed down the centuries ever since. Some claim them as proto-socialists, others as anarchistic radicals, but either way Putney set the terms of the argument for almost 370 years – an argument that is still going on today.

After Charles was executed in 1649, England (soon to be joined, whether they liked it or not, by Scotland and Ireland) became a republic called ‘The Commonwealth of England’. A limited form of Parliamentary democracy was now in practise and it finally seemed like the tyranny of absolute monarchs that had begun with the Norman invasion in 1066 was over.

However, grand words are just that – words. After the army smashed the Scots and invaded Ireland, they were in no mood to compromise with anyone about anything and the purging of anti-army MPs from Parliament, Cromwell’s elevation to ‘Lord Protector’, and the military dictatorship that followed turned hopes of a peaceful, tolerant, and free English republic to dust.

After the death of Cromwell in 1658 it was ironically part of the army itself, led by General George Monck (who had been cunningly keeping out of things up in Scotland), that helped usher in the return of the monarchy in 1660.

But absolute monarchy had had its day in England and, following the invasion of the William of Orange’s Dutch forces in the ‘Glorious Revolution’ in 1688, England’s one and only true “revolution” came to a close with the constitutional monarchy that still stands, more or less in the same shape, today.

A panoramic view of the battlefield from the Naseby Memorial, Northamptonshire