London, 1643 – a city under threat, a resurgent enemy, dangers around every corner. And a poet, engaged by a king to lead a plot to restore him to his throne…

The year 1643 would prove to be the ‘high water mark’ of the Royalist cause in the first English Civil War. Only months after the inconclusive Battle of Edgehill in October 1642, the King seemed to have the upper hand, both politically and militarily. Thanks to defeats handed out to the Parliamentarian armies of Sir William Waller and the Earl of Stamford, and Prince Rupert aiming to confront and destroy the prevaricating Earl of Essex’s main field army, the King now sought to exploit political divisions amongst his opponents in London and weaken their cause. Between late February and late April, Parliament took measures to stiffen its cause while it faced a difficult military situation and it was during this time that Charles encouraged the development of what became known as The Waller Plot…

Born in 1605 at Colshill in Hertfordshire, by the 1640s Edmund Waller had become a notable MP and poet. His father died when he was a baby but left him well-off, while his uncle on his mother’s side was politician and future Ship Money rebel John Hampden. His separate lives as a politician and a poet began virtually at the same time: he was 18 when he wrote his first poem – ‘Of the Danger His Majesty (Being Prince) Escaped in the Road at St. Andero’ about the then-Prince Charles – and became MP for Amersham around the same time. He was reelected for the Short Parliament and then became MP for St Ives in the Long Parliament.

Born in 1605 at Colshill in Hertfordshire, by the 1640s Edmund Waller had become a notable MP and poet. His father died when he was a baby but left him well-off, while his uncle on his mother’s side was politician and future Ship Money rebel John Hampden. His separate lives as a politician and a poet began virtually at the same time: he was 18 when he wrote his first poem – ‘Of the Danger His Majesty (Being Prince) Escaped in the Road at St. Andero’ about the then-Prince Charles – and became MP for Amersham around the same time. He was reelected for the Short Parliament and then became MP for St Ives in the Long Parliament.

Initially a supporter of John Pym, the King’s chief critic in Parliament, he then moved over to a group of moderates led by Viscount Falkland and Edward Hyde – although Waller was careful to avoid directly criticising the king, these were definitely not arch-Royalists and opposed Charles’ brand of absolute monarchy. Yet Waller became increasingly concerned over Parliament’s attempts to interfere with the Royal prerogative and, as tensions between King and Parliament increased, he gravitated towards the King while also urging Parliament to seek an accommodation with him to avoid open conflict. He remained in Parliament after the outbreak of the Civil War, still arguing on behalf of the Crown.

Plots and the uncovering of them were virtually ten-a-penny in 1640s London and, following the collapse of peace talks in March 1643 and as Parliament took important measures to shore up its military situation, Charles gave encouragement to a plan to deliver London to him by stealth…

Waller was one of the commissioners nominated by Parliament to negotiate with the King at Oxford, although he was not trusted to be one of the principle negotiators. When the commissioners were presented to Charles, Dr Johnson later recounted that the King said to Waller “Though you are the last, you are not the lowest nor the least in my favour.” This was later taken to be either a subtle acknowledgement of the plot’s existence or a kind word from his monarch which then gave Waller the idea for the conspiracy. Either way, Charles already had a reputation for duplicitousness – seeming to encourage reconciliation in good faith while secretly plotting to gain the upper hand – and it was a characteristic that would later lead him to the scaffold.

Once back in London, Waller began plotting with his reluctant brother-in-law, Nathanial Tomkins (an influential London man, MP for Carlisle and Christchurch, and clerk to Queen Henrietta Maria’s Council) and a wealthy linen draper called Richard Chaloner. Not without some justification, they believed there were strong support for peace in London, as well as moderate factions in Parliament who were still hopeful of a reconciliation with Charles I. According to Clarendon, the plot aimed to create a groundswell of Royalist support in the city and then force Parliament to negotiate by withholding the taxes it desperately relied on to fun the war. As chief conspirator, Waller’s impressive list of contacts included the Earl of Northumberland, John Selden, Bulstrode Whitelocke and Simonds D’Ewes, all of them prominent Puritan critics of Charles l’s government.

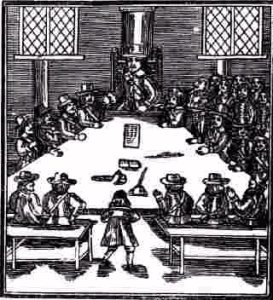

They proceeded with great caution – only three conspirators met in one place, and no man was allowed to reveal the plot to more than two others, so that if any were suspected or seized no more than three others could endangered. The bibliophile politician Lord Conway joined in the plot and they conspired to conduct a census of those in London who secretly supported the King – a conspirator was to be appointed in every district to distinguish between friends of the king, adherents to the parliament, and neutrals. Parliamentarian leader John Pym later claimed that the results of their survey showed that within the walls of London there was one Royalist for every three Parliamentarians, but outside the walls it was one for Parliament against five for the King.

But while the plot seems to have begun as a means to peacefully force Parliament to seek a negotiated settlement, it soon developed into plans for an armed rising – the King issued a commission to 17 prominent London citizens, empowering them to lead an armed rising on his behalf. The Tower of London and strong points in the city would be captured and leading Parliamentarians were to be seized in their beds as a prelude to a general uprising by Royalist supporters before the gates were thrown open to troops sent from Oxford.

The plot was soon betrayed by one of Tomkins’s servants, possibly due to the boasting of loose-lipped conspirators, but news of the discovery was deliberately withheld by the Parliamentarian leadership for full propaganda effect: it was revealed theatrically on the official fast day of 31 May, when MPs were summoned from morning worship. Despite the culprits being already arrested, a precautionary mustering of the militia caused a considerable stir in the city.

The exposure of the King’s duplicity in negotiating while encouraging an armed uprising in the city did his cause considerable harm and the parliamentary leadership was quick to seize the initiative. As Ian Roy detailed in ”This Proud Unthankefull City’: A Cavalier View of London in the Civil War’ in London and the Civil War (1996): “a day of thanksgiving was ordered, to praise the Lord and His mercies to embattled London (now miraculously pre-served from imminent destruction), and Pym at last was able to gain acceptance for his long-wished-for scheme to impose a binding, and divinely sanctioned, loyalty oath upon his followers. In June a vow and covenant was made law, by which all men could dedicate themselves anew to the cause of parliament.’ Harsh measures followed. The royal peace messengers, whose incautious boasts had alerted the authorities in the first place, were arrested and died in prison … The houses and goods of those citizens named in the commission were seized.”

Once in captivity, Waller quickly turned informer against his fellow conspirators, making an “abject speech of recantation” before the Commons and – following examination by the Earl of Manchester and other commissioners – provided a full confession of “whatever he had said heard, thought or seen, and all that he knew… or suspected of others”. He then bought his way out of trouble – he paid bribes to leading members of the Commons and, after spending a year and a half in the Tower of London without trial, was fined £10,000 (effectively a year’s income) and allowed to go into exile in November 1644.

Tomkins and Challoner were less wealthy and less fortunate. Both sticking to their principles, they were tried and then hanged outside Tomkins’ home on Fetter Lane in London on 5 July 1643, their bodies were then exposed to the public gaze. Speaking from the scaffold, Tomkins blamed his involvement on his affection for his brother-in-law and loyalty to the King, but denied that he was an atheist or a Catholic: “I have sometimes had conferences and disputes with some Jesuits (in foreign parts chiefly). I thank God my principles of religion were so grounded they could never shake me. I have been called by some of them an heretic in grain. But … in regard of some relations, and in regard I received very civil usage from those of that religion in foreign parts … I returned the like civility to them here as I had occasion.”

The theatrical revelation of the Waller Plot was used to justify the imposition of a new ‘Vow and Covenant’ to shore up support for the continued war effort. It threatened that there was a “popish and traitorous plot, for the subversion of the true Protestant reformed religion, and the liberty of the subject”, pursued by a Roman Catholic army demonstrated by the “treacherous and horrid design lately discovered, by the great blessing and especial providence of God … all who are true-hearted and lovers of their country should bind themselves each to other in a Sacred Vow and Covenant”. In God’s Fury, England’s Fire: A New History of the English Civil Wars, Michael Braddick says “subscribers were to acknowledge these distractions to be a punishment for their sins, and to promise not to lay down arms while the papists were in arms; to disavow the late plot and report any future ones; and most importantly, ‘according to my power and vocation, assist the forces raised and continued by both Houses of Parliament, against the forces raised by the King without their consent’. By declaring that ‘I do believe, in my conscience, that the forces raised by the two Houses of Parliament are raised and continued for their just defence, and for the defence of the true Protestant religion, and liberties of the subject, against the forces raised by the King’, the Vow had in effect dropped claims that the armies were fighting for the defence of the King’s honour and person. This was made the substance of a separate short declaration of ‘loyalty to the King’s person, his crown and dignity”.

This meant the moderate ‘Peace Party’ in Parliament was almost fatally compromised and hopes of a peaceful settlement to the war were dashed as those who had pushed for a negotiated peace were forced to disavow any sympathy for the plotters’ aims and to reaffirm their support for military action through the Vow and Covenant. Many prominent waverers and secret sympathisers fled the capital, making their way to the King’s court at Oxford, and a string of Royalist victories in the summer of 1643 only hastened the flow as Parliament’s military situation worsened. In London, the plot – and others that arose throughout the year – stoked fears of a Royalist Fifth Column only too eager to open the gates to the invader. Royalist captives were temporarily held in prison hulks in the Thames, there were moves to create a new army with a fresh commander, military control of London was transferred from the Earl of Essex to Lord Mayor Pennington.

For his exile, Waller chose Roan in France before moving to Paris, and then Switzerland, taking his new wife Mary with him. In 1645 his poems were first published in London as he travelled in Europe with the writer and diarist John Evelyn. During the worst period of his exile he had to sell his wife’s jewels to maintain himself but remained hopeful of a reconciliation with the Commonwealth government. In part thanks to the support of his near-relations Oliver Cromwell and Adrian Scrope, the Rump Parliament allowed him to return to England in January 1652. He had good relations with Cromwell, to whom he published A Panegyric to my Lord Protector in 1653, and was made a Commissioner for Trade a month or two later. He wrote several other poems in support of Cromwell and the Protectorate over the next few years, until the Restoration in 1660. Waller expressed his support for Charles II with his 1660 poem To the King, upon his Majesty’s Happy Return. Challenged by the new king to explain why it was inferior to his eulogy of Cromwell, the poet replied, “Sir, we poets never succeed so well in writing truth as in fiction”.

Waller was returned to the Cavalier Parliament in 1661 as MP for Hastings and soon become a familiar face, a moderate MP who refused to give unalloyed support to any administration and supported religious toleration at a time when non-conformism was often regarded with suspicion. Interestingly, he attempted to act as a broker between the factions that developed between 1678 and 1681 around the Popish Plot, the fictitious conspiracy concocted by Titus Oates that whipped up anti-Catholic hysteria, but he found little success and later withdrew from active politics.

Waller was returned to the Cavalier Parliament in 1661 as MP for Hastings and soon become a familiar face, a moderate MP who refused to give unalloyed support to any administration and supported religious toleration at a time when non-conformism was often regarded with suspicion. Interestingly, he attempted to act as a broker between the factions that developed between 1678 and 1681 around the Popish Plot, the fictitious conspiracy concocted by Titus Oates that whipped up anti-Catholic hysteria, but he found little success and later withdrew from active politics.

Waller’s poems were widely read during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and enjoyed a revival in the early 20th; a 1717 engraving by George Vertue showed him alongside the prominent English poets Samuel Butler, John Milton, Abraham Cowley and Geoffrey Chaucer.

He died at home in in Buckinghamshire, surrounded by his family, on 21 October 1687, and was buried in the churchyard of St Mary and All Saints Church, Beaconsfield.

Sources:

David Scott – Politics and War in the Three Stuart Kingdoms, 1637-49 (2003)

Michael Braddick – ‘History, Liberty, Reformation and The Cause: Parliamentarian military and ideological escalation in 1643’ (in The Experience of Revolution in Stuart Britain and Ireland (2011), ed: MJ Braddick, David L. Smith)

Michael Braddick – God’s Fury, England’s Fire: A New History of the English Civil Wars (2009)

Stephen Porter (ed.) – London and the Civil War (1996)

Prince Rupert’s naval career began during the Second Civil War of 1648 when he joined Charles, Prince of Wales in an unsuccessful naval exedition using Parliamentarian ships that had defected to the Royalists during the naval revolt of 1648. Retreating to the neutral port of Helvoetsluys in the Netherlands, Rupert – now appointed admiral – was blocked until November 1648 when he began a new career as a privateer, raiding English merchantmen to help raise funds for his uncle Charles I’s soon-to-be-literally-cut-short cause.

Prince Rupert’s naval career began during the Second Civil War of 1648 when he joined Charles, Prince of Wales in an unsuccessful naval exedition using Parliamentarian ships that had defected to the Royalists during the naval revolt of 1648. Retreating to the neutral port of Helvoetsluys in the Netherlands, Rupert – now appointed admiral – was blocked until November 1648 when he began a new career as a privateer, raiding English merchantmen to help raise funds for his uncle Charles I’s soon-to-be-literally-cut-short cause. Blake is one of the less well-known figures of this period, but he helped establish British supremacy at sea that would last for centuries.

Blake is one of the less well-known figures of this period, but he helped establish British supremacy at sea that would last for centuries. But the party would soon be over. In early 1650, England’s new Council of State denounced Rupert as a pirate and commissioned Blake to destroy the Royalist squadron. Blake sailed from Portsmouth in March 1650 with a powerful fleet of fifteen ships. They arrived at Cascaes Bay at the mouth of the River Tagus on 10 March 1650 and Blake immediately demanded the use of Lisbon harbour and Portugal’s co-operation against Rupert’s pirates – his answer was warning shots fired from Portuguese forts when he tried to sail up the river.

But the party would soon be over. In early 1650, England’s new Council of State denounced Rupert as a pirate and commissioned Blake to destroy the Royalist squadron. Blake sailed from Portsmouth in March 1650 with a powerful fleet of fifteen ships. They arrived at Cascaes Bay at the mouth of the River Tagus on 10 March 1650 and Blake immediately demanded the use of Lisbon harbour and Portugal’s co-operation against Rupert’s pirates – his answer was warning shots fired from Portuguese forts when he tried to sail up the river.

Cavandish led his army out of Newcastle in pursuit of the Scots. The two sides met but bad weather made a battle impossible and the Marquess retreated into the Royalist stronghold of Durham.

Cavandish led his army out of Newcastle in pursuit of the Scots. The two sides met but bad weather made a battle impossible and the Marquess retreated into the Royalist stronghold of Durham.